The day has finally arrived…I have finished my third Little French Jacket and I am now excited to find places to wear it!

We just returned from a wonderful four-week vacation that saw us taking a ship through the Panama Canal and spending a few weeks tooling along the west coast of South America, spending a week in Peru and just over a week in Chile. That meant that I had to put my couture sewing work on hold for a while, but there are two very good outcomes from this. First, I am very excited to have returned and to see my LFJ with fresh eyes. In addition, I learned all about alpaca wool fabric and sweaters so will share that insight eventually. But now, here’s how I finished that jacket.

When last I posted, I had finished the sleeves along with their trim and hand-finished the silk charmeuse lining. What is left at this stage is the really creative, fun part: making it my own with buttons and pockets.

I ordered a selection of buttons from China (perhaps not the best idea I’ve ever had) but the quality was not exactly as I might have hoped. However, they’ll be great for smaller projects. They were also very late arriving so in my impatience, I headed down to Queen Street West here in Toronto to a favourite spot for button selection (Neveren’s Sewing Supplies) and spent a bit of quality time rummaging through hundreds of styles. I came home with another selection then set about determining the look I was going for.

In the end, I decided that the buttons should make a subtle statement reflecting the gold chain that I would be stitching along the hem line in due course.

But first, I have to tell you about the debacle of the buttonholes.

Way back at the beginning of this process I made a decision to go with hand-worked buttonholes, a process that I would have to learn since I’ve never done them before. Well, that didn’t work out so well, so I did some tests of machine buttonholes on the fabric and lining and was satisfied. However, when the time came to actually complete those buttonholes, I realized that I had not taken into consideration the bulk of the seam allowance when I did those samples. It simply was not going to work. I was now in a real pickle. It was too late to do the faux-welts on the interior, the technique that Claire Schaeffer recommends in both this pattern (Vogue 8804)  and in her book, so what to do? I was left only one choice: doing hand-worked buttonholes through both the fabric and lining, an approach that you do, indeed sometimes see in couture garments, but that when done by an amateur can look dreadful. I would have to spend some time learning. So, I made up some samples and start the process. It took me two weeks.

and in her book, so what to do? I was left only one choice: doing hand-worked buttonholes through both the fabric and lining, an approach that you do, indeed sometimes see in couture garments, but that when done by an amateur can look dreadful. I would have to spend some time learning. So, I made up some samples and start the process. It took me two weeks.

According to the Yorkshire Tailor whose video I shared in an earlier post, you have to do about 30 such buttonholes before you get it right. He has a point. For the first six that I did (using waxed button twist) I made a variety of mistakes. On each occasion I corrected that mistake for the next one until I finally thought I had corrected them all. After about a dozen samples, I decided they were all right so I started with the sleeves. They were okay, but not terrific. The truth is, however, that the thread matches so well that you can hardly see the buttonholes at all anyway. Then it was on to the front.

I took a deep breath and began. The scary part is after the initial preparation of the spot by hand-basting around it to ensure stability while sewing when you have to cut the hole open. At that point there is no going back. It’s not like machine button holes where you cut them after they’re completed. No, these ones have to be cut before you begin since the whole point of them is that the edges are completely covered by the stitches thereby avoiding any of those little strings that can be such a problem in machine buttonholes.

When they were finally completed, I sighed a big sigh of relief and sewed on the buttons. I was not 100% happy with them, but 80% was going to have to do for this first attempt. I’ll do them again on another project and look for perfection. When that was done, it was time to place the four pockets.

Some patterns suggest that you do this before the buttons are in place. I figured that if I did it that way I would run the risk of the pockets looking too crowded with the buttons. This way I could actually see the finished product.

So, I pinned them in place then hand-sewed them to the jacket using double-stranded silk thread for a bit of stability. The final step, of course, is the hem-line chain, a feature of Chanel’s jackets.

Originally inserted as a practical way of weighing down the jacket edges, the chain is now really more of a style statement. However, in the case of this jacket, the extra weight will be welcome. I sew the chain on using short lengths of doubled silk tread with one stitch in each link. These stitches, when done properly, are hidden under the link. I use short lengths in case the chain ever comes loose (which it has done in one of my previous jackets). The short lengths mean that it will only come away for a short distance to be fixed.

The chain is completed, so that can only mean one thing: I finally have a jacket!

The first thing I have to do at this stage in the process of creating my Little French Jacket is review the pattern instructions for finishing the lining by hand and trimming. I know how to do this, but the pattern designer (Claire Schaeffer, Vogue 8804) has her own views that actually differ slightly from my experience.

The first thing I have to do at this stage in the process of creating my Little French Jacket is review the pattern instructions for finishing the lining by hand and trimming. I know how to do this, but the pattern designer (Claire Schaeffer, Vogue 8804) has her own views that actually differ slightly from my experience.

Whenever I see a fantastic jacket of any sort, I always wonder exactly what is underneath that beautifully finished exterior. What does it look like between the lining and the fabric? What precisely is it that keeps those edges straight? How is it that the sleeve cap is so perfect? Oh, I know all about underlining, seam finishing, sleeve setting and all the rest, but putting it all together to achieve a specific finish – well, that’s the thing. And that’s why the stabilizing and other aspects of what goes between what the world will see – the lovely bouclé – and what I will feel – the even lovelier silk charmeuse – is at the heart of my next step.

Whenever I see a fantastic jacket of any sort, I always wonder exactly what is underneath that beautifully finished exterior. What does it look like between the lining and the fabric? What precisely is it that keeps those edges straight? How is it that the sleeve cap is so perfect? Oh, I know all about underlining, seam finishing, sleeve setting and all the rest, but putting it all together to achieve a specific finish – well, that’s the thing. And that’s why the stabilizing and other aspects of what goes between what the world will see – the lovely bouclé – and what I will feel – the even lovelier silk charmeuse – is at the heart of my next step.

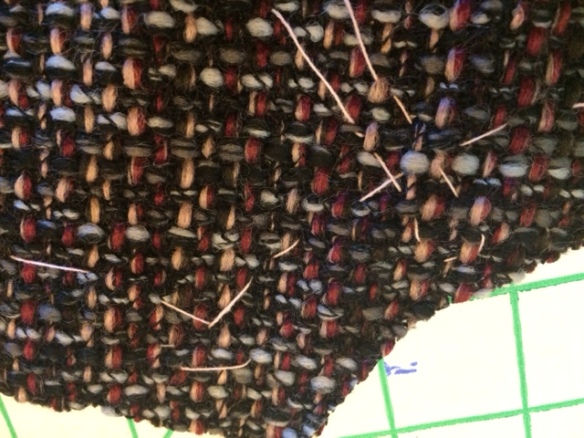

The more expensive the fabric, I buy, the more trepidation I feel just at that moment when, shears in hand, I hover above the swath of fabric on the table in front of me. I have already prepared the tweed bouclé by steaming it within an inch of its life, and I have carefully laid it out, in a single layer to ensure accuracy. I have carefully measured the grain lines and pinned them precisely where they are supposed to be. But this time around – on this third Little French Jacket – I’m using a slightly different approach to cutting. Rather than simply following a seam allowance, I’m just doing a rough cut. I’ll be marking seam lines and using those for a more accurate fit. And yet, here I sit, shears at the ready, taking a moment to pause and breathe before that first snip. Once that’s underway, I’m committed. Here I go.

The more expensive the fabric, I buy, the more trepidation I feel just at that moment when, shears in hand, I hover above the swath of fabric on the table in front of me. I have already prepared the tweed bouclé by steaming it within an inch of its life, and I have carefully laid it out, in a single layer to ensure accuracy. I have carefully measured the grain lines and pinned them precisely where they are supposed to be. But this time around – on this third Little French Jacket – I’m using a slightly different approach to cutting. Rather than simply following a seam allowance, I’m just doing a rough cut. I’ll be marking seam lines and using those for a more accurate fit. And yet, here I sit, shears at the ready, taking a moment to pause and breathe before that first snip. Once that’s underway, I’m committed. Here I go.

It’s important at this juncture to say that I am also being careful not to cut through any of the selvages. I am preserving them because they are fringed. I don’t know yet how I’ll trim this jacket — that’s a design decision for later. But I do know that I might want this fringe at a later date.

It’s important at this juncture to say that I am also being careful not to cut through any of the selvages. I am preserving them because they are fringed. I don’t know yet how I’ll trim this jacket — that’s a design decision for later. But I do know that I might want this fringe at a later date.

Coco Chanel is often quoted as having said, “Dress shabbily and they remember the dress; dress impeccably and they remember the woman.” And nothing says impeccable dressing to me more than perfect fit. Oh how I strive for perfect fit (as anyone who has read previous posts on this journey with me will know!). As I advance down the road toward Little French Jacket #3, I am faced squarely with fitting a new design rather than reusing an already fitted one. Of course this begins with the muslin.

Coco Chanel is often quoted as having said, “Dress shabbily and they remember the dress; dress impeccably and they remember the woman.” And nothing says impeccable dressing to me more than perfect fit. Oh how I strive for perfect fit (as anyone who has read previous posts on this journey with me will know!). As I advance down the road toward Little French Jacket #3, I am faced squarely with fitting a new design rather than reusing an already fitted one. Of course this begins with the muslin.

For example, until recently, I had been under the mistaken impression that Jacqueline Kennedy was wearing a favourite Chanel suit on that fateful day in 1963 when JFK was assassinated beside her in the back seat of a convertible in Dallas, Texas. In fact, her suit was an authorized copy from New York-based chez Ninon, a knock-off that was 1/10 the price of an original, and made in the USA. There are those who continue to believe that Jackie was wearing an original Chanel, but to me it’s more plausible that since she was the American first lady, and her husband evidently urged her to buy American, that the suit was an official Chanel copy. In that way it was authentic from its design to its bouclé, the fabric that has become synonymous with the Little French Jacket – which brings me to my next step toward my third LFJ: now that I have the design I’m going for, I need fabric.

For example, until recently, I had been under the mistaken impression that Jacqueline Kennedy was wearing a favourite Chanel suit on that fateful day in 1963 when JFK was assassinated beside her in the back seat of a convertible in Dallas, Texas. In fact, her suit was an authorized copy from New York-based chez Ninon, a knock-off that was 1/10 the price of an original, and made in the USA. There are those who continue to believe that Jackie was wearing an original Chanel, but to me it’s more plausible that since she was the American first lady, and her husband evidently urged her to buy American, that the suit was an official Chanel copy. In that way it was authentic from its design to its bouclé, the fabric that has become synonymous with the Little French Jacket – which brings me to my next step toward my third LFJ: now that I have the design I’m going for, I need fabric.

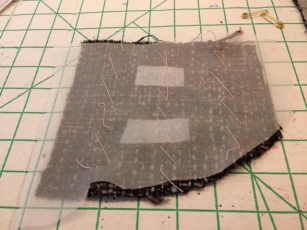

With fabric selected and at the ready, I tissue-fit the pattern and cut the first muslin. Let’s just say that the fit of the first muslin is hideous.

With fabric selected and at the ready, I tissue-fit the pattern and cut the first muslin. Let’s just say that the fit of the first muslin is hideous.

You must be logged in to post a comment.